Before I get into the specific games I want to analyse, I want to discuss a topic that I think is very important, and which I’ll keep referring to when I analyse games on this blog.

You may have noticed that Owlboy is a 2D game that uses pixel art. We often say in interviews that we think that there is more to be explored in the 2D medium, and that that’s the reason why we chose the style we’re currently using. But what do we mean by that? Surely there is also much to be explored in 3D, too? Why, then, do we continue with 2D?

The answer is of course that we see a lot of unused potential in 2D, and specifically in low resolution. Most 2D games are created in as high a resolution as possible these days, and we wanted to go in the opposite direction. Here’s some justification for why one might choose that direction.

The advantages of specifying less

Have you ever seen a film where you hated the ending, or where the ending ruined the sense of mystery that the film had for you? Have you ever read a book, and then upon seeing a film version you felt that the character didn’t work at all for you anymore?

Congratulations! You have been the victim of specificity!

Many pieces of fiction work well because the telling of the story has specifically excluded details that would have jeopardised the our enjoyment of the narrative. We don’t want an action tale where we follow the hero to the bathroom, or a love story where lots of time is spent describing a particularly unattractive feature of one of the love birds’ appearance. Ideally in a piece of fiction, we are shown the thematically relevant details and details that build up the atmosphere that we are trying to establish.

Seems obvious enough! How does this relate to Owlboy?

In games, the opposite is currently the status quo. Worlds are made as rich and expansive as possible, and the graphics as detailed as possible. It’s natural, in a sense, because games don’t suffer from being too long, nor does a highly detailed character model have to be distracting in the same way that a long, boring, descriptive paragraph would be in a book. However, the more realistic detail you show your world in, the more you are replacing abstractions with specific details.

This is a design choice. The best choice is not always to specify more; sometimes it is better to specify less. Let’s do some basic exploration of that notion.

Introducing abstraction to games

So we now know that we will often want to reduce complexity by abstracting away parts of our games. How does one go about doing that? Let’s take a concrete example.

Let’s say you have a character who you want to be mysterious, and need to convey this through how the character is shown in the game. How do we solve this issue? Well, we could simply not show the character’s face or facial expressions. Not so hard! Now we are provided with a sense of distance to the character. Very mysterious!

But what if we want the character’s face and emotions to be visible? Suddenly the situation is difficult. We could try to underscore some sense of mystery in the specifics of what the character says, or in the character’s voice – but this is suddenly very fragile. It relies on good writing, and a good voice actor. And what about localised versions of the game? The dubbing and translation would have to be spot on for the effect to carry over. We could give the character a facial expression that hints at whatever mystery we have concocted – but what if we want to show other emotions too?

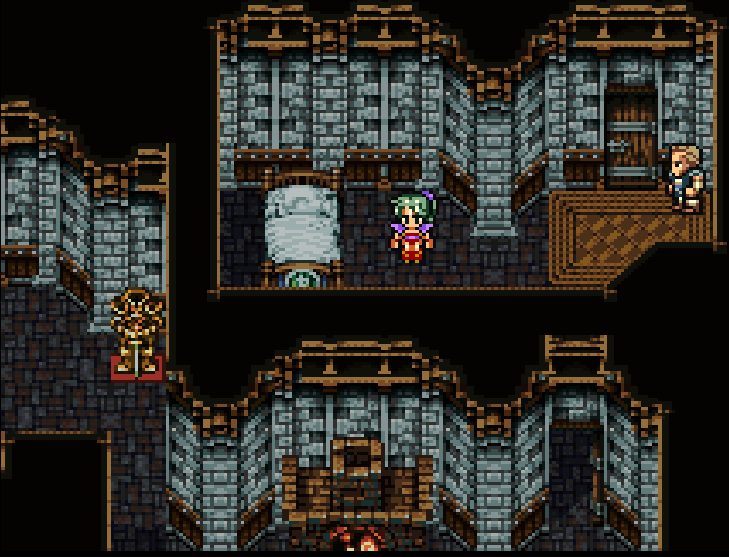

Let’s see what Final Fantasy 3 did in this situation.

In the 2D medium with low resolution graphics, the solution becomes much simpler. By default, the camera cannot be moved. This means that the character’s face is small, and subtle emotions cannot be conveyed in cutscenes. This means that the emotions we do show (through the music, or through a limited number of expressive animations) carry more weight. Added to that, your brain fills in the facial expressions for the characters in various scenes – meaning that the blank face in the screenshot has become an abstraction for any range of facial expressions, emotions and attitudes that you can project onto Terra.

Whether you approve of pixel art or not, it is clear that the design problem of characterizing someone like Terra is suddenly much easier. The low resolution gives us an art style that cannot show the subtleties that we don’t want to give away or specify. We can hide away the parts that we want to remain hidden, and show the parts that should be in focus. Terra’s emotional crisis is clear, yet what and who she is remains a mystery, despite her being in plain view. To show what happens when we remove this abstraction from Final Fantasy 3, here is concept art of Terra in Final Fantasy Dissidia.

Now, this isn’t how I pictured Terra by a long shot – in fact, I doubt that I would enjoy Final Fantasy 3′s opening sequence if this were the character I was following, regardless of how much I love that scene in its current form. Subjective opinions aside, with a character this detailed, it’s difficult to create the mysterious character that we described. The character’s emphasis is shifted as we remove the abstractions of pixel graphics.

Now, this isn’t how I pictured Terra by a long shot – in fact, I doubt that I would enjoy Final Fantasy 3′s opening sequence if this were the character I was following, regardless of how much I love that scene in its current form. Subjective opinions aside, with a character this detailed, it’s difficult to create the mysterious character that we described. The character’s emphasis is shifted as we remove the abstractions of pixel graphics.

I should clarify that I don’t think pixel graphics or increased abstraction are a silver bullet, or that pixel Terra is objectively better than Dissidia-Terra. However, the principle seems to often be overlooked in gaming: increased abstraction and ambiguity can help tremendously with telling a story.

The principle, of course, also applies to gameplay. When you don’t have to show the player’s every action in great detail, you’re a lot more free as to how you implement various mechanics. Many games these days, like Assassin’s Creed, feature fighting systems where you basically press a button at the right time to make your character kill an enemy in a spectacular, gory cutscene. The reason is that the fighting has to look like real fighting – yet there is no way to make intuitive controls for the finishing moves that the assassins pull off. In this way, the graphical realism leads to less physical gameplay with lower player involvement.

Finally, some things to consider

Thanks for staying with me so far! That was a brief introduction to some of my reasons for liking pixel-based games. Before I close out the post, here is some more food for thought:

- What does this mean for making games child/family-friendly? Could more abstract art styles make it possible to make a game that both children and adults can find enjoyable? Is this harder to achieve with more detailed, high-definition games?

- How many of the advantages and disadvantages of 2D over 3D stem from some kind of innate difference between the formats, and how much stems from the way that we do 3D currently?

- One final clarification: I’ve been equating pixel art with reduced detail for a while now. This is somewhat misleading. Pixel art can be incredibly detailed – but it is one abstraction further away from realism, hence it presents the world with less realism. Pixel art can be extraordinarily realistic and detailed – however, the point of this post was to show that it can lend itself nicely to introducing helpful abstractions as well.

Fun stuff to think about. I’ll be writing more stuff like this (though hopefully shorter) in the weeks to come, whenever I find some spare time.

See you then!

Great post! Same could be said for animation. How many times have you seen animation struggeling for realism but ending up being stiff and dull. If you simplify the animation with for example a cartoonish look and feel, people let it go! There is nothing we humans know better than reality, so try to take them as far away as possible! Also, personally I think pixel art or simplified images could be more educational, because it forces the brain to fill out the blanks. Just like books! Don’t give everything away on a silver platter. It spoils the fun and don’t leave some parts to the imagination. ^_^

I’ve had experience where lowering the resolution and framerate of a movie made it better.

In the movie Shoot ‘Em Up there is a scene where they jump out of an airplane and fight in mid air.

To me it screamed crappy blue-screen effects when I watched the DVD-version.

But when looking at an Xvid copy which had a lower resolution and a lower framerate the scene looked much better.

Not sure if this is related but your post reminded me of this. It has baffled me for a very long time.

That is quite interesting. Lot of people don’t like the 48fps version of The Hobbit, compared to the 24fps. Some tv’s make “artificial” frames between frames, with up to 128 fps (I think). I once saw Lord of the Rings in a store once, with this “smart motion” setting turned on. Everything looked fake and cheap. Maybe our brain actually like to “fill out the blanks” and don’t get everything served, just like in pixel art!

Yeah, I akways thought pixel 2d games had something special, never occured to me it was because of “specificity” Thats why even monster puppets in 80s movies are sometimes better than CGI todays.