This is going to be a bit of an unusual post. I’ve considered writing this since I tried the demo of Undertale a few weeks ago, and at this point, I’m fairly convinced that Undertale is a considerably more valuable game than most of what’s been announced this year.

as a warning, I will be going through elements that are spoilers from the demo, so if you’re planning on reading this, I absolutely recommend you try out the demo for yourself here before reading this. It doesn’t take long to complete. You’ll have time to do this.

To start off, I think I should mention that I’m a big fan of creative mechanics. More so, mechanics that play into a game’s themes. I feel most recent games that attempt to tell a story have decided to rely on a few set mechanics. The most typical examples have the player character shown in first-person, or in third person. You have buttons for basic attacks or interaction, and other characters are walking around the same world you are, and will respond to said interactions.

Now, whether this is due to the developer enjoying this type of design, or because they feel like they need a template to make it easier to tell their story, this is never the less the most common way of presenting narrative. In fact, I’m sure a lot of you are already wondering if this is even something to object to. It seems to make sense to do things this way, but a number of games have employed vastly different tactics, and I feel it’s a shame this is a design choice we’ve stopped questioning.

If I am to use quick example, Earthbound for the SNES did something a little different. On the surface, it looks like a standard RPG set in an abstract version of the US, but underneath it all, what made the game special was how they blended it’s themes into everything.

The game is literally an abstraction of the US. Here, you don’t walk up to your enemies and press the punch button. You enter into a turn based system where regular every day objects are given battle effects. You buy a hamburger? You put ketchup on it and it becomes tastier and you heal more. Your enemy is a fan of a pop singer? Throw a magazine at them to distract them. Your enemies are regular people or objects that get angry or are out of control. Normal feelings of comfort granted by a teddy bear is contextualised into providing literal damage protection during the abstract version of a real-life conflict.

A plethora of everyday instances share this bridge. If you want to heal yourself, you can call for a pizza delivery, and like in real life, you have to actually wait for it to arrive. Instead of a standard health bar, in this game it’s themed after a slot machine that slowly ticks down, allowing for lucky numbers and the option to heal yourself before it ticks all the way down.

While the idea of providing an inventive context to normal life is interesting, all these elements are centered around the same premise: What does it feel like to live in the US? What does the KKK living outside your city feel like? How bizarre that must be. Why do Americans put condiments on their fast food? What does riding the bus cross country feel like? To the Japanese developers, they wanted to not only explore, but demonstrate this feeling. But they didn’t do it through long cut scenes or by the statements made by the people in the world. All the mechanics in the game are to some effect a play on American culture. It’s a very simple design strategy and yet it’s rarely explored beyond the game’s theme.

Which brings me to Undertale. -SPOILERS START HERE BY THE WAY-

Booting up the demo, I had no expectations from the game. I had simply decided I wanted to try something that day. At the start of the game, you’re placed in a dark pit. The first thing I noticed was that your main character, a child, had no gender traits. Given what the game is centred around, I think it was wise to make the character so that anyone can embody themselves in it. Usually, gender is not an issue for me in games, but in this particular case, I think it was useful as the connection needs to be strong for what is to come later.

The first character you meet seems perfectly innocent. You’re being put through a quick tutorial in the battle system. Then, immediately, you are taught it’s relevance. This character is here to kill you. In fact, you’re told everyone is here to kill you. You are betrayed. As you sit there and wait to die, you’re saved by a large, female character called Toriel, which knocks away your attacker like he’s nothing. She says she’s here to protect you and will help guide you to safety.

Now. I have just been demonstrated that things in this place want and will kill me, even something small and insignificant can achieve this. And suddenly, here is a giant goat lady with visible fangs that can destroy the thing that can kill me easily and says she wants to help me.

“This person is going to betray me too.” And that sets the theme for the entire game.

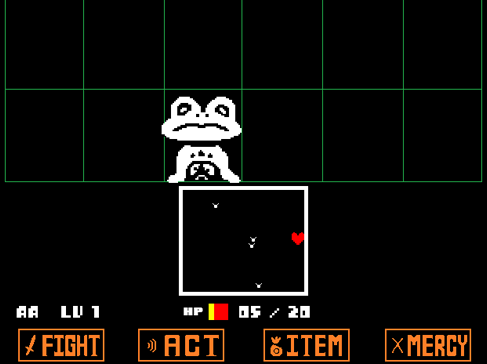

Betrayal and trust will from here on be interwoven with everything. You will be taken into random, turn based battles with enemies as you progress through the game. Following how easily you were attacked the first time, your first instinct is to attack and kill your enemies. To avoid damage, you dodge waves of bullet particles fired at your heart in a contained box. Every enemy has their own themed attack bullet, and most enemies will demonstrate their personality through their attack.

As you progress, you realise that some enemies have problems. Problems you can play into. Some enemies react to flirting. Some don’t like being teased. Some will just spontaneously start dancing and won’t care that you leave the battle altogether. The battle mechanics in other words play on the same theme of trust and betrayal. You gradually learn to know your enemies as characters and what they want. Putting in effort could allow you to avoid fighting altogether. So now, you’re on this dodgy in between place where you could potentially trust things, even if they want to hurt you.

Then there’s Toriel.

At the start, she takes care of you to the point of redundancy. You’re being lead into a room where you have to solve a puzzle, but Toriel solves it for you so you don’t have to. You have a spike pit you need to walk across, but Toriel holds your hand to cross it. She leaves you in a hallway and hides behind a pillar to see if you’re brave enough to walk through a room alone.

The entire sequence paints her a the most caring mother figure possible, and yet, as my instincts tell me, she’s going to betray me. It’s become common in games that the nice character always has a twist at the end and this just means I’m playing to get duped.

I’m left alone for a moment, and end up fighting a ghost boss. Reading into his crying attacks, I cheer him on until he’s happy and leaves me alone. Everything in the first scene is being counteracted, and I’m expecting a twist as a result.

Finally, I get to Toriel’s house. This is where she attacks.

She doesn’t. I’m given a nap. When I wake up there’s cake waiting for me. Toriel is reading by a fireplace. It’s an amazingly well crafted feeling of home and I can’t help but be suckered into the tranquility. Then it happens. I ask if I can go home. Toriel runs off. I knew it.

I follow her to the basement. She’s going to destroy my only exit because if I leave her house, she reasons I’ll just die. Not as bad of a betrayal as I expected, but hey! I was right! This initiates a fight and I have to take her down. There is no option to settle things non-violently. A strange feeling given the options I had before.

That’s when the brilliant happens.

I’m not strong enough to fight her. I’m about to die, and I can’t escape. And through the abstraction the game has based it’s mechanics on, Toriel suddenly visibly moves all her bullets away from me, letting me punch at her while she keeps me safe. The result is I end up killing her. As I leave the room, the same character that betrayed me at the start of the game sits there and laughs at my face as the demo ends.

I need to note a couple of things at this point.

The first is that the game pulled something I didn’t even remotely expect. The good character was actually good. Toriel was presented as a counter to the immediately established theme that in this game, people will betray you. All the mechanics, all your items are centered around this theme. You heal yourself with free candy put out by strangers which could be an easy trick. Your conflicts can or can not be resolved non-violently. Toriel does absolutely everything in her power to help and protect you, and through the same mechanics that demonstrated how you would get betrayed decided to sacrifice her own life in order to keep you safe.

The second point, and one that is a little strange to write about: I was legitimately depressed for three days after playing this demo.

I’ve had a rough time growing up. I won’t claim myself as any special case, far from it, but I’ve had my share of emotional turmoil. I play video games like other people read books, and it’s really been a while since a game legitimately struck me. A lot of games attempt to create characters you care for, but in most cases, it’s a verbal demonstration. You’re told you should like this person and the people in question will state they care about you, but it’s rarely demonstrated, and in games that use generalised mechanics of storytelling, these points are rarely emphasized.

Toriel demonstrated something I feel a lot of us feel we lack. Someone that demonstrates they care about you without a “but” at the end. That feeling safe could actually be justified for once. I feel that’s a very rare quality in a video game.

It should be noted that after I had completed the game, and started researching to write this article, I realised there was a way to resolve the conflict without killing Toriel. It requires a lot of guesswork, but it is actually possible. I don’t feel this detracts from my experience at all. This is not the expected ending, and Toriel has already demonstrated a type of care as a character that is surprisingly unusual.

Most games are about protecting or caring for someone else. Being cared for is an unusual role reversal, and I think provides something we haven’t tapped into yet as game designers.

I feel many games can learn a thing or two from Undertale.